What is frontotemporal dementia?

Frontotemporal dementia, or FTD, is a neurodegenerative disease that affects adults, with an average age of onset between 50 and 60. It is the commonest form of dementia below the age of 60 but can occur from the 20’s until the 90’s. It is equally common in men and women, and the lifetime risk of developing FTD is 1 in 750.

Watch this video to understand the difference between FTD and other dementias:

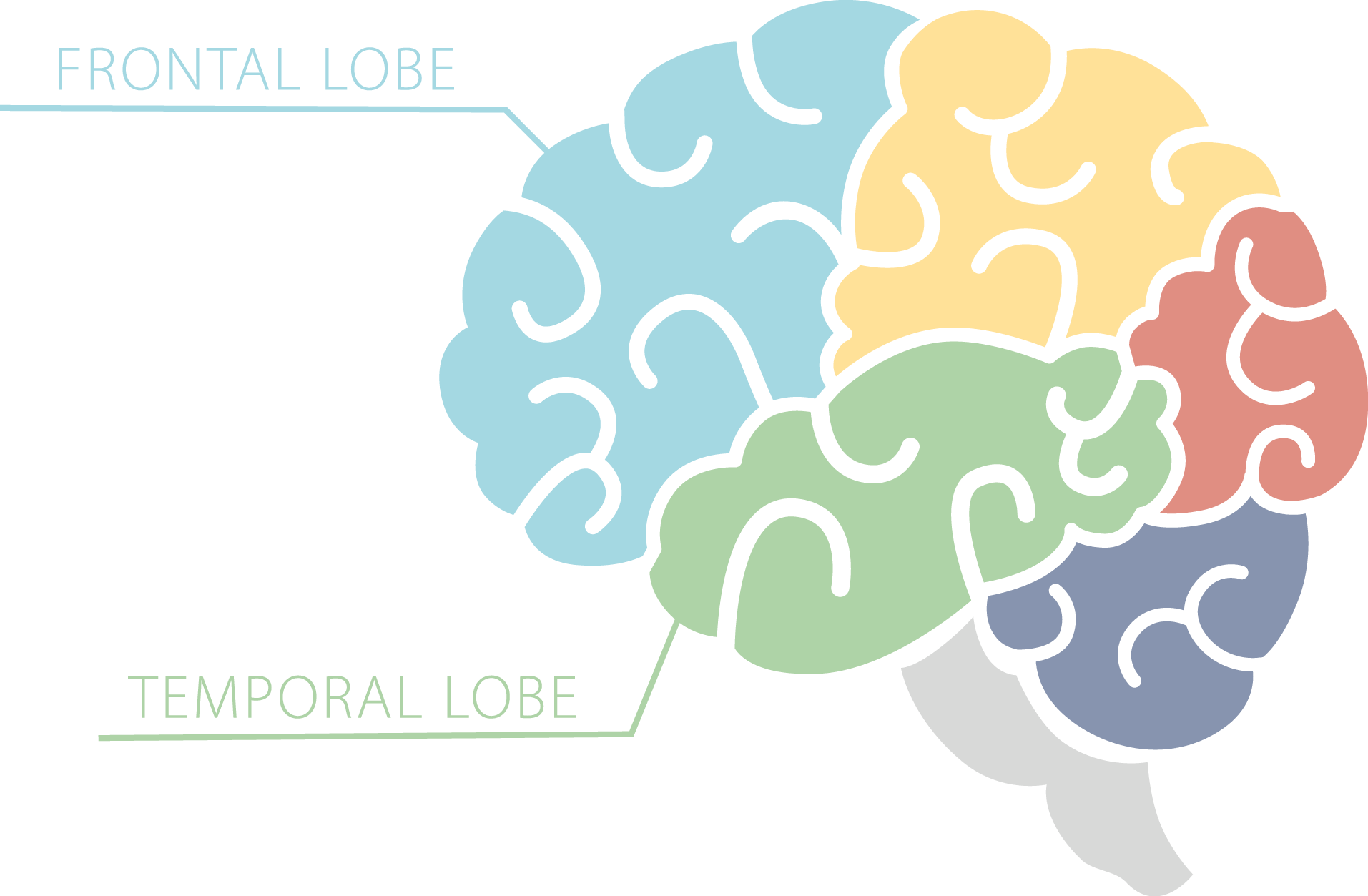

FTD gets its name because it affects the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. It is therefore sometimes also called frontotemporal lobar degeneration or FTLD. The disorder used to be called Pick’s disease, and this name is occasionally still used.

In about a third of people with FTD the disease is caused by an abnormal gene that has been passed on from one generation to another, a pattern of inheritance known as autosomal dominant. It remains unclear exactly why the other two thirds of people with FTD develop the condition.

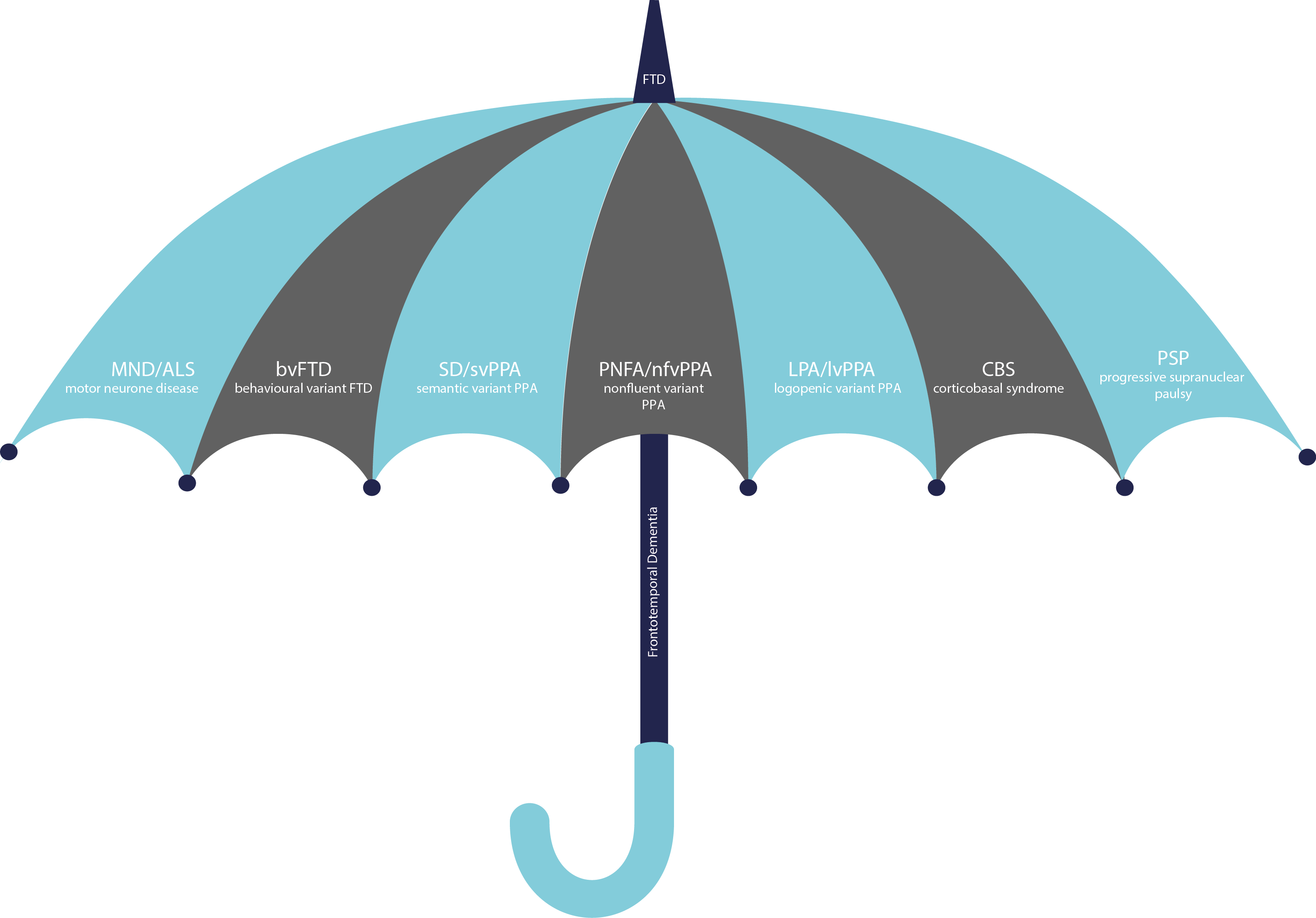

FTD is actually a group of disorders that overlap with each other. Usually the first symptoms are either changes in people’s behaviour, which we call behavioural variant FTD, or impairment in their language skills, which we call primary progressive aphasia, or PPA. PPA can be further split into a number of other subtypes, known as the semantic, nonfluent and logopenic variants.

Some people with FTD may also develop disorders that affect movement of the body. Motor neurone disease or MND, is a disease that affects the motor nerves, causing weakness of the muscles that control the limbs, speech and swallowing. It is also called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. Parkinsonian disorders are a group of conditions similar to Parkinson’s disease in that they cause stiffness and slowing of movement rather than weakness. These are also sometimes called parkinsonism. Two particular parkinsonian disorders overlap with FTD, called corticobasal syndrome, or CBS, and progressive supranuclear palsy, or PSP.

History

The Czech neurologist Arnold Pick first described people with personality change and language impairment associated with loss of brain cells in the frontal and temporal lobes in 1892. However, although there were occasional reports of similar cases in the early part of the 20th century, progressive behavioural and language problems were largely neglected by doctors for many years.

The first modern accounts of progressive language disorders in the Western literature were by Elizabeth Warrington in 1975 and Marsel Mesulam in 1982. Warrington described a group of people who had developed problems with semantic memory, what we would now call semantic variant PPA or semantic dementia. Mesulam independently wrote about patients who had developed language problems, which he initially called slowly progressive aphasia.

The increased understanding of these conditions over the following years culminated in research groups from Lund, Sweden and Manchester, UK defining criteria for diagnosis firstly in 1994 and then in an updated version in 1998. These criteria defined the three main conditions of semantic dementia, progressive nonfluent aphasia (or nonfluent variant PPA) and the behavioural disorder of FTD. These criteria, commonly called after the first author David Neary, stood until recently, when an international consortium of research groups came together to define new criteria for behavioural variant FTD and the PPA subtypes.

Clinical syndromes

Behavioural variant FTD, or bvFTD, is the commonest of the FTD syndromes. It usually presents with a change in personality or behaviour and difficulties with the part of thinking that helps with planning and problem solving, called executive function.

Symptoms include socially inappropriate behaviour such as being more disinhibited or losing manners, withdrawing from social life and becoming more apathetic, and becoming less sympathetic or empathic to other people. People may also become very obsessive or develop rituals, and sometimes their appetite changes, becoming interested only in certain types of food, particularly sweet things. Very occasionally people may develop odd delusional thoughts and have visual hallucinations.

Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, memory is usually not affected in the early stages but there may be problems with executive function and understanding of others’ emotions.

Watch a video from Dr Jonathan Rohrer describing the features of bvFTD:

Semantic variant PPA or semantic dementia is a disorder of semantic knowledge, in other words our understanding of concepts and facts. The first symptoms are usually language problems such as difficulty finding the right word, or losing the meaning of words – people may ask what a previously known word means, for example “What is a tornado?” Other symptoms include the inability to recognise objects, called an associative agnosia, or faces, called a prosopagnosia. As the disease progresses behavioural symptoms similar to bvFTD can develop.

Nonfluent variant PPA or progressive nonfluent aphasia is a disorder that causes people to have difficulty producing speech. In some people this is because of a problem with grammar, causing them to use the incorrect tense or missing out words like ‘the’ or ‘and’, called agrammatism. In other people it is because of a difficulty in planning how the speech muscles will produce words, called apraxia of speech, causing people to have difficulty articulating words or stutter. Unlike SD, understanding of words is not affected in the early stages. Some research groups think that PNFA can be subdivided further into 2 or 3 subtypes.

Logopenic variant PPA or logopenic aphasia is a disorder where people have difficulty finding the right words to say, often stopping mid-sentence. They may also have difficulty holding things in mind for a long time. Although it is considered one of the PPA variants, it is usually caused by an atypical form of Alzheimer’s disease rather than FTD.

Patients with bvFTD or PNFA may also develop one of the parkinsonian disorders. Symptoms of corticobasal syndrome include stiffness of the muscles and slowness of movements more on one side of the body than the other, known as rigidity and bradykinesia. Occasional brief jerking of the muscles, or myoclonus, may occur. People may also have greater difficulty co-ordinating particular movements, known as limb apraxia. This disorder is also sometimes called corticobasal degeneration.

Symptoms of progressive supranuclear palsy include balance problems, falls, stiffness particularly of the neck and trunk muscles, and difficulty moving the eyes up and down.

About 10% of people with FTD will also develop amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neurone disease, causing weakness in the legs, arms and in the muscles that control speech, swallowing and breathing. This occurs in association with bvFTD, occasionally with nonfluent variant PPA, and only very rarely with semantic variant PPA.

Genetics

About a third of people with FTD will have a family history of the disorder with around a quarter having an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Of the different clinical syndromes, bvFTD is the most likely to run in the family, whilst svPPA only very rarely runs in the family.

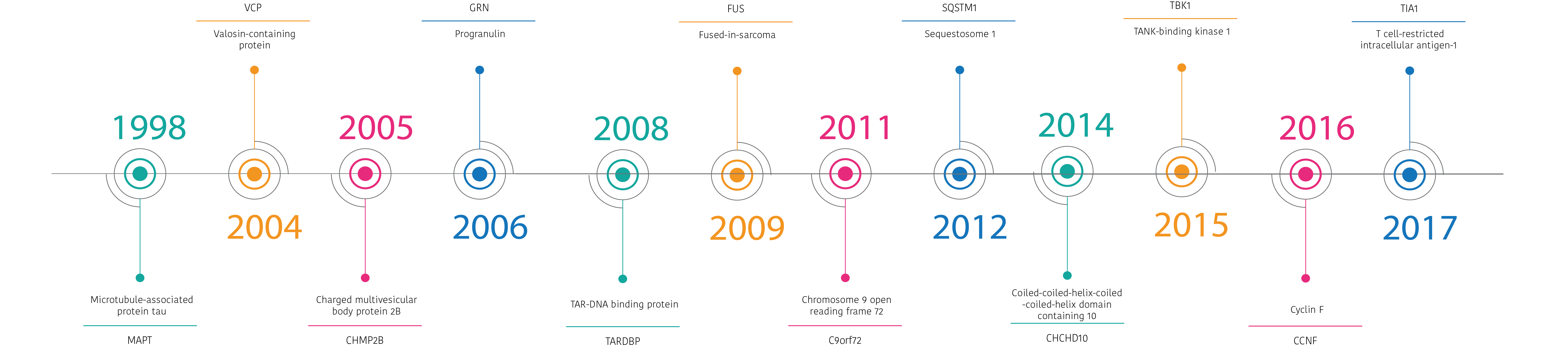

There are quite a few genes that are associated with FTD but only three are common. These are called microtubule-associated protein tau or MAPT, progranulin or GRN, and C9orf72. Mutations in each gene vary in how frequent they are across different countries, but across the world the most common genetic group is C9orf72.

Mutations in other genes are only very rare causes of FTD. These include TANK-binding kinase 1 or TBK1, transactive response DNA binding protein or TARDBP, valosin-containing protein or VCP, and charged multivesicular body protein 2B or CHMP2B.

A number of genes do not directly cause FTD but can modify the type of symptoms or age at which those symptoms develop. These include TMEM106B.

Pathology

At post mortem a number of different abnormal proteins are seen in the brain. The three key proteins are called tau, TDP-43 and FUS, each of which has a number of subtypes.

The common tau subtypes are Pick’s disease, corticobasal degeneration or CBD, progressive supranuclear palsy or PSP, and the pathology associated with MAPT mutations.

The subtypes of TDP-43 are called A, B, C, D and E. Type A is associated with progranulin mutations, whilst C9orf72 expansions are associated with both type A and B.

There is not a clear one to one association of a clinical syndrome with a particular pathology. Behavioural variant FTD is the most heterogeneous of the clinical syndromes and can be caused by any of the pathologies. SvPPA is usually caused by TDP type C whilst nfvPPA is associated with Pick’s disease, CBD, PSP or TDP type A or B.

Neuroimaging

FTD is associated with loss of brain cells, or atrophy, in the frontal and temporal lobes. This can be seen with magnetic resonance imaging or MRI.

Patients with bvFTD often have atrophy more on the right side of the brain compared to the left although the exact pattern varies by the genetic or pathological subtype. As well as the frontal and temporal lobes, other areas of the brain that are affected are the insula and the cingulate, and areas deeper in the brain including the basal ganglia and thalamus.

Patients with svPPA have predominantly temporal lobe atrophy, usually more marked in the left hemisphere, whilst in nfvPPA, the atrophy is seen initially in the left frontal lobe and insula. In lvPPA the atrophy is seen in the posterior part of the left temporal lobe and the parietal lobe.

In CBS, the atrophy usually affects the frontal and parietal lobes, more on one side than the other, whilst in PSP an area called the midbrain, the top part of the brainstem which connects the brain to the spinal cord, is affected.

Other ways to image the brain including positron emission tomography or PET imaging, and single-photon emission computed tomography or SPECT imaging.

Investigations

As well as brain imaging, other tests are often done to help diagnose FTD.

Testing for specific genetic mutations with a blood test can be performed in certain centres. In families of patients with known mutations, genetic counselling is important for other members of the family if they want to think about presymptomatic genetic testing.

Lumbar punctures or spinal taps allow examination of cerebrospinal fluid or CSF. There are currently no specific markers of FTD in the spinal fluid but CSF testing can help exclude Alzheimer’s disease.

Management

There are currently no curative treatments for any of the FTD syndromes although some clinical trials are now under way.

Selective serotonin uptake inhibitors or SSRIs are often used in bvFTD to help with behavioural symptoms although their effect is relatively small. Neuroleptic drugs should be avoided where possible, as patients with FTD are often sensitive to side effects. The drugs used in Alzheimer’s disease such as the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors may make some behavioural symptoms worse.

Supportive management is important and includes speech and language therapy with communication aids in PPA, behavioural management strategies such as establishing routines and home modification, and respite when needed for carers.

Click here to find our Frequently Asked Questions and our Glossary of all the different medical terms used on FTD talk.